What is Adult Day Care service?

The definition and current issues in Japan 2022 Edition

[CONTENTS] Introduction Definition - Public System for Adult Day Care - Budget System for the LTC Insurance - Who uses ADC? - Facilities(Agencies) - Staff members Issues - Outline - Others References Acknowledgments

Introduction

Purpose of this page

There have been no English-language reports that comprehensively explain Japan’s Adult day care (ADC) centers. Therefore, the purpose of this report is to function as an English-language resource, supervised by Takashi Naruse at a level that can be cited academically. The content of this report should be easy to understand not only for specialists but also for general readers. I categorized the contents into definitions and issues, organized the details into chapters, and checked for quotation marks, which should be updated approximately once a year. The revision history is announced on this webpage. Of course, revision history should be properly archived and published on this website.

Citation; Takashi Naruse and Masayuki Kobayashi, What is Adult Day Care service? The definition and current management issues in Japan 2022. September 2022. [https://takanaruse.com/en/ideas-editorials-opinions/what-is-adult-day-care-service/].

Handling of the word ‘ADC’

ADC is recognized as a long-term care service in Japan. In this report, ADC is used as one of the long-term care (LTC) services, and ADC is a service where nursing and social care are provided to disabled older people. Transportation by the agency’s car from clients’ homes to and from the facility is included in ADC service [1*].

Definition – Public system for Adult Day Care

LTC service clients use two systems

In Japan, the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare (MHLW) encourages the disabled older population to appraise and adopt relevant services depending on their needs [2]; it supports such encouragement to help this population group reach independence in the performance of their activities of daily living (ADL) [4*].

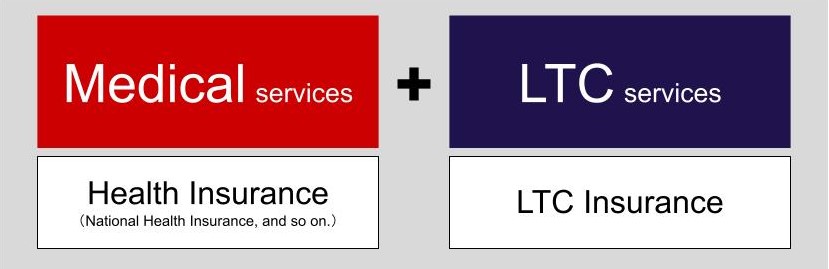

With some exceptions, residents of Japan enroll in health insurance to receive medical care from doctors and nurses at hospitals and clinics. Those aged 40 years and over must enroll in long-term care insurance to receive LTC. Therefore, clients of LTC services, including ADC, use the two systems.

History of the Long-term care system in Japan

In Japan, in the 1950s, a welfare service dispatched staff to the homes of elderly people during the reconstruction period after the end of the war (1945). It was not until the 1960s that facilities and services were developed under the government’s welfare policies for the elderly. In the 1970s, healthcare costs for the elderly increased, necessitating a review of the system. One of the main reasons for this was the introduction of free healthcare for the elderly (almost everyone aged 70 years and over) in 1973. The ‘social hospitalization’ of lonely elderly people for social interaction was also identified as a problem in this free healthcare system. By way of background, short stays were established in 1978 and ADC services in 1979. In the 1980s, the so-called bedridden elderly was reported in many media reports and became a social problem. In the 1990s, preparations were made to introduce a long-term care insurance system that started in 2000. Long-term care insurance, to which people aged 40 and over were entitled, financed all public services, including ADCs. The system was updated and maintained [3*].

Definition – Budget System for the LTC Insurance

Key points of this chapter

The structure of the LTC system in Japan is complicated and difficult to imagine for people living overseas.

・Half of the budget for providing LTC services is spent on the Japanese government, prefectures, and municipal taxes. [3*]

・Half of the budget for providing LTC services consists of monthly payments, depending on the clients living in the municipalities. [6*]

・Self-pay (10% to 30%) [3*]

Details of these rules are explained in the next section. There are no ADC-specific rules for taxes, monthly payments, or out-of-pocket expenses. In this chapter, it is important to understand that the budget of the ADC depends on the local financial systems of the municipalities, similar to other LTC services for the elderly.

Different monthly payments for each municipality, tax burden, and self-pay

In Japan, there are differences in monthly payments for LTC insurance depending on the clients living in the 47 prefectures and municipalities (cities, wards, towns, and villages). Each municipality controls monthly payments by creating a three-year plan according to the population composition of residents over the age of 40, who are obliged to have insurance. The denominator in the formula for monthly payments is the number of residents aged 65 years and over. This is one reason why monthly payments differ by municipality. There is a strong relationship between insurance costs and salary levels in municipalities [6*].

The next section explains public funds. Half of the financial resources (the budget for providing services to clients) come from the taxes of the Japanese government, prefectures, and municipalities [3*]. The tax balance is also stipulated by the LTC Insurance Act.

The flow of financial resources is illustrated in detail in the following URL (Japanese only, accessed September 2022).

https://www.mhlw.go.jp/topics/kaigo/zaisei/sikumi_02.html

Although the diagram shown on this website is very complicated, it is a structure for the overall optimization of providing LTC services to all citizens. An important point for experts and researchers is that each municipality has its own independent management structure but uses one format. According to a statistics report by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, as of 2021, there will be 1,571 municipalities managing long-term care insurance systems [7*].

The last point is self-pay. Under this rule, elderly people bear 10%–30% of the LTC service fee. The share to be borne depends on the seniors’ income, savings, and assets, including public pensions.

Definition – Who uses ADC?

Reception and subsequent process at municipalities

If an elderly person in Japan wishes to receive ADC services, the first step is to inquire at the LTC insurance reception desk in the municipality. In general, officials examine their independence using a checklist for disability certification. After the check, a doctor’s written opinion is attached and certification work is carried out. Elderly people choose the services they want to use based on their certified disability level. There is also a system that supports care-management professionals.

Clients can receive support to formulate a comprehensive care plan to use medical and welfare services. Clients can undertake this support by the Regional Comprehensive Support Centre or Designated In-Home LTC Support Providers (so-called Care Centre), but their location and convenience will differ depending on the municipality.

![Table1; Summary chart for the certification in Japan of the level of help or care needed [9*]](https://takanaruse.com/en/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Summary-chart-for-the-certification-inJapan-of-the-level-of-help-or-care-needed.jpg)

ADC clients’ experiences and research status to date

ADC services consist of the following four elements: social participation, hygiene and health, exercise and eating habits, and family support. This was in line with reports in international reviews that providers had four general objectives when offering ADC services: (i) providing social and preventive services, (ii) supporting clients’ continued independence, (iii) supporting clients’ health and daily living needs, and (iv) enabling family caregivers to take a break (from daily care) and/or continue with their employments [10*].

The J-AdaCa Tool (Japanese clients’ experiences during adult day care service use) was developed to assess the richness of Japanese clients’ experiences during ADC services [11*].

In the latest study, a wide variety of communication occurred as part of social interactions (social interactive events) in ADCs; clients communicated in shades of human relationships, ranging from light chats to serious counseling about their problems, sometimes taking a catastrophic defensive posture in front of the audience. However, there was a negative feeling of having trouble knowing what to do [12*].

In addition to individual/group rehabilitation exercises, activities (coloring, mah-jong, dancing, singing, calligraphy, craft, etc.) are offered based on individual preferences. In general, clients spend five to seven hours on rehabilitation exercises, activities, and group lunches. If possible and required, the client was bathed.

Definition – Facilities(Agencies)

In principle

The first point to keep in mind in this chapter is that quality assurance in LTC settings supports older persons to continue living safely and comfortably [13*]. ADC is a generic term for aged care; it comprises building-based services that offer a wide variety of programs and amenities for older people [10*].

Facility installation status, room regulations, rules for service content, and classification of the service provision time

In Japan, there are approximately 48,000 ADC facilities, as of 2020. Half of these are operated by for-profit corporations, accounting for more than 70% of community-based ADC facilities. More than 40% of ADC facilities for dementia have been established and operated by social welfare corporations. There is a facility standard that requires the dining room and functional training room (each or even in the same place) to be spacious. In addition, there are rules to ensure that conversations at the consultation site for daily life are not overlooked.

The services provided included bathing, excretion, meals, lifestyle consultation and advice, health checks, other daily life care, and functional training. There is also a maximum number of clients that can be accommodated per day. The service provision time has a classification rule of 3 h to 9 h, with the exception of 2 h or more, and less than 3 h. This category does not include the pick-up and drop-off times [14*].

Definition – Staff members

In principle

The term ADC staff in Japan defines not only caregivers but also staff members, including management staff (including facility maintenance and building owners). However, professionals who assist in care plans (so-called care managers) are excluded from the definition in this chapter.

Job description of ADC staff members

ADC staff pick up and drop off clients in large vehicles. In addition to driving back and forth between the facility and clients’ homes, they also assist in getting on and off (some facilities have dedicated drivers). The ADC staff welcomes clients to the facility and provides health checks, bathing, meals, toilet assistance, and functional training. It is based on a care plan (predefined service plan) that corresponds to each client’s classification of the service provision time. Care content, services, and outcomes vary from client to client, and staff members must document them. There are standards for the number of staff with professional qualifications in life counseling, nursing, rehabilitation, massage, and management. Unqualified staff can work under the guidance of qualified staff members [2*].

Intervention-related benefits to clients by ADC staff members

Intervention-related benefits include improved physical, mental, and social functioning, exposure to comprehensive care, improved well-being, and alleviation of family caregivers’ burdens [10*] [15*] [16*].

Issues – Outline

Overview

LTC services are one of the approaches which promote the health of disabled persons. Reports have found an increase in the proportion of LTC recipients living at home, which is a major consequence of rapidly aging populations in OECD countries, including Japan. Expenditure on LTC share of the gross domestic product (GDP) has increased more rapidly than any other healthcare expenditure, and the annual growth rate during the 2005–2015 period was 4.6% across OECD countries [17*].

Hence, these countries have witnessed a growing interest in adult day care (ADC) services, centers, and agencies for the older population with disabilities. Social participation was the most common objective for 75% of ADC clients, and it might be important to fulfill clients’ socialization needs [18*].

ADC was the most popular type of LTC service among the Japanese disabled population; in April 2018, with 1.13 million ADC clients [19*], approximately 26.8% of the disabled population. For your reference, about 12% of the aged population (65 years or older) in Japan used one or more LTC services in April 2018 [20*].

Issues – Others

Discussion of additional contents

The following additional items are currently being considered and discussed.

・ADC community formation and exploring

・Professional education and research

・Bringing in and popularization of ICT tools

・An objective summary of the impact of COVID-19

・A video introduction of activities conducted at ADC

References

1. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Tsushokaigo oyobi Ryoyotsushokaigo (Adult day care, in Japanese), document at the 141st Social Security Examination Committee, Sub-Committee on Health Care Benefits. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/05-Shingikai-12601000-Seisakutoukatsukan-Sanjikanshitsu_Shakaihoshoutantou/0000168705.pdf (Accessed on 12 September 2022) 2. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Tsuusyorihabiri KouhyousareteiruKaigo service nitsuite (Official type of LCT services in Japanese) Available online:https://www.kaigokensaku.mhlw.go.jp/publish (Accessed on 12 September 2022) 3. Health and Welfare Bureau for the Elderly. Nihonnokaigohokenseidonitsuite, in Japan available online:https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/policy/care-welfare/care-welfare-elderly/dl/ltcisj_j.pdf (Accessed on 12 September 2022) 4. Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. The Long-Term Care Insurance System, Long-Term Care Insurance in Japan. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/topics/elderly/care/2.html (Accessed on 1 September 2022). 5. Fujiwara, M.; Abe, K. Zaitakukoureishougaishano tsushosabisuriyouigi: ADLnouryoku to ribyokikan niyorukentou (Meaning of Day-care and/or Day-service for the elderly with physical disabilities: Influence of ADL and duration of illness in Japanese). 6. J. Jpn. Occup. Ther. Assoc. 2002, 21, 240–250. [Google Scholar]Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. 7. Zenkokunochiikibetsukaigohokenryotokyuhusuijunwokohyoshimasu (Public announcement of payment and monthly salary levels for LTC insurance each municipalities in Japanese) Available online:https://www.mhlw.go.jp/topics/kaigo/osirase/tp040531-1.html (Accessed on 12 September 2022). 8. Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Zenkokutoukeihyo Hokenjabetsu dai1pyo dai1gouhihokenjasu Reiwa3nen1gatubun (Table1 Total number of Category 1 insured persons, the LTC Insurance Services Status Report during January 2022, in Japanese) Available online:https://www.mhlw.go.jp/topics/kaigo/osirase/jigyo/m21/2101.html (Accessed on 1 September 2022). 9. Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare.Service usage fee. in Japanese available online:https://www.kaigokensaku.mhlw.go.jp/commentary/fee.html (Accessed on 1 September 2022). Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Sankouzuhyou-sankou(3) Kaigohokenseidoniokeruyoukaigoninteinoshikumi (Reference 3, The certification of the level of help or care needed under the LTC insurance system in Japanese) Available online:https://www.mhlw.go.jp/topics/kaigo/kentou/15kourei/sankou3.html (Accessed on 5 September 2022) 10. Orellana, K.; Manthorpe, J.; Tinker, A. Day centres for older people: A systematically conducted scoping review of literature about their benefits, purposes and how they are perceived. Ageing Soc. 2020, 40, 73–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version] 11. Naruse, T.; Tuckett, A.G.; Matsumoto, H.; Yamamoto-Mitani, N. Measurement Development for Japanese Clients’ Experiences during Adult Day Care Service Use (The J-AdaCa Tool). Healthcare 2020, 8, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] 12. Naruse, T.; Hatsushi, M.; Kato, J. Experiences of Disabled Older Adults in Tokyo's Adult Day Care Centers during COVID-19-A Case Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, doi:10.3390/ijerph19095356. 13. OECD. Health at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2017; Available online: https://doi.org/10.1787/health_glance-2017-en (accessed on 21 January 2020). 14. Health and Welfare Bureau for the Elderly. Kaigo service shisetsu・Jigyouchyousa (LTC service facility and business survey in Japan) Available online:https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/24-22-2.html (Accessed on 5 September 2022). 15. Ellen, M.E.; Demaio, P.; Lange, A.; Wilson, M.G. Adult Day Center Programs and Their Associated Outcomes on Clients, Caregivers, and the Health System: A Scoping Review. The Gerontologist 2017, 57, e85-e94,doi:10.1093/geront/gnw165. 16. Fields, N.L.; Anderson, K.A.; Dabelko-Schoeny, H. The Effectiveness of Adult Day Services for Older Adults. Journal of Applied Gerontology 2014, 33, 130-163, doi:10.1177/0733464812443308. 17. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Health at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] 18. Takashi Naruse *, Noriko Yamamoto-Mitani. Service Use Objectives among Older Adult Day Care Clients with Disability in Japan. Nurs. Rep. 2021, 11(3), 608-614. 19. Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Heisei29nendo Kaigokyuhuhitoujittaichosano Gaikyou (Statistics of Long-Term Care Benefit Expenditures, April 2018 in Japanese). Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/kaigo/kyufu/17/index.html (accessed on 12 September 2022). 20. Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Heisei 30nendo Kaigokyuhuhito Jittaitoukei no Gaikyo, Heisei30nendo 5gatsushinsabun-heisei31nen4gatsushinsabun (Statistics of Long-term Care Benefit Expenditures, May 2018 to April 2019 in Japanese) Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/itiran/eiyaku.html (accessed on 12 September 2022).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing, and Hakononakanohako, General Incorporated Association (https://hakononaka.jp/) for their professional web content management.