CASE REPORT

Peer Support Program: A Buddhist Priest Driven Workshop for Family Caregivers of Older People with Disabilities, “Kaigoshano kokorono yasuragi cafe”

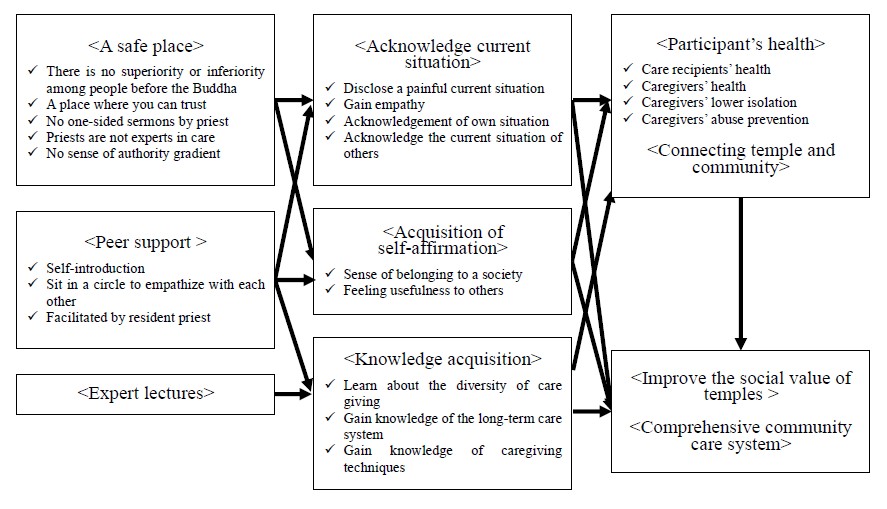

Abstract: Temples are widespread in Japan and they operate regardless of urbanity. In 2016, a peer support program for family caregivers was launched at a Pure Land Buddhist temple in Tokyo (Kaigoshano Kokorono Yasuragi Cafe (Carers’ relaxing cafe). According to the logic model we developed, the program comprises “peer support” and “lectures by experts.” We highlight that “the temple is a safe place,” participants can “acknowledge each other for their current situation” and “gain self-affirmation and knowledge.” This experience is expected to contribute to the health of caregivers and care recipients and the bond between the temple and the community in the long run. It was assumed that, as a result, this experience would lead to the “improvement of the social value of temples” and “realization of comprehensive care in the community.” As the number of older people with diverse cultural backgrounds requiring care is expected to increase in the future, further verification of the significance of peer support programs for caregivers held at temples will be necessary.

Keywords: Buddhist priests; Caregivers in Japan; Japanese Temples; Community Support; Kaigoshano kokorono Yasuragi Cafe

Citation; Takashi Naruse1, Tatsuro Shimomura2 and Masakazu Hatsushi3. Peer Support Program: A Buddhist Priest Driven Workshop for Family Caregivers of Older People with Disabilities, “Kaigoshano kokorono yasuragi cafe” November 2022. [https://takanaruse.com/en/ideas-editorials-opinions/yasuragi-cafe/]. Affiliation; 1: Division of Care Innovation, Global Nursing Research Center, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo. 2: Hakononakanohako, General Incorporated Association. 3: Konenji temple of Jodo sect (representative officer), a research team of the Jodo Shu

1. Introduction

As the number of older people in Japan increases, the government promotes community-based comprehensive care. Community-based comprehensive care represents an effort to meet the various needs of residents who might require nursing care based on collaboration between professionals and non-professionals. The long-term care insurance system covers various types of professional care services; however, there is concern about a lack of professional service resources, especially in the rural community.

In this report, we will introduce a peer support program for family caregivers implemented by a temple as one of the advanced approaches to community-based comprehensive care; “Kaigoshano kokorono Yasuragi Cafe (Carers’ relaxing cafe).” This program has already been introduced partially in Buddhist books and local TV shows. However, it has neither been introduced internationally for health professionals [1] nor explained with a logical structure. We will present the program and its logic model here because it is crucial as a case report on the development of community care based on various cultural considerations.

2. Context of the Program

Approximately 6,690,000 older people in Japan in 2019 needed nursing care [2]. Approximately 56% of them were estimated to be cared for by family members who lived with them [3]. The caregiving burden threatens their health [4]. Thus, alleviating their burden is expected to protect their own health and contribute to sustained family caregiving. This will help older people with disabilities to continue living in their homes.

There were approximately 77,000 Buddhist temples in 2020 in Japan [5]. It is twice the number of Adult Day Care centers (approximately 38,000 centers in 2015 [6]) and Christian churches [5]. They can be considered familiar semi-public institutions for Japanese community residents. Since before the Meiji era, temples have been the center of intellectual activities and interaction among residents in the community [7]. Recently, after the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, there has been considerable rise in active discussions about the value of temples as community resources [7]. The Jodo sect is one of the prominent Buddhist sects in Japan. This sect is open to all people, and accepts people with other religious beliefs. Its temple has large rooms where community people can gather, discuss, and help each other. In general, large parking spaces are prepared so that many people can visit there.

“Kaigoshano kokorono Yasuragi Cafe (KYC)” is a peer support program. The KYC program was implemented in 2016. It was developed by Tatsuro Shimomura with the aid of his colleagues of Jodo shu Research Institute, and Tasuro is the head priest of a Jodo-Buddhist temple, Konenji [1]. In 2016, Mr. Shimomura visited a peer support program for family caregivers driven by a professional long-term care service facility in Chiba prefecture. He was informed that caregivers needed help in their community. However, there was a lack of public resources for family caregivers, especially in rural regions without enough public resources, and it was challenging for public organizations to cover the needs gaps. Mr. Shimomura and his colleagues discussed their contribution to community needs gap and started the KYC program.

Program contents

The KYC program aimed to offer an opportunity to participants so that they could share their experiences in caregiving. The program’s objective and content were developed through an overview of other caregiver peer support programs in professional long-term care service agencies and discussions with priests in other temples.

In the Konenji-temple (Figure 1), priests had the KYC program every two months between 2016 and 2019. Participants were approximately 15 people, and nearly all of them were 40 years or older. Participants visited a reception room (Figure 2) in Konenji-temple. Priests welcomed participants and facilitated them to encourage peer support interaction.

During the first 30 minutes, participants were required to introduce themselves shortly in a few minutes. They explained why they were participating and what they felt about caregiving. In this period, participants sat in a meeting discussion style with tables, and the presenter stood up on the spot. Each participant was expected to learn about the diversity of caregivers’ experiences and others who had similar feelings and experiences. In case someone had difficulty talking, the priest was present to support them. Giving each person an equal opportunity to speak was expected to motivate the participants.

Here are three representative topics that participants used to present their experience:

The difficulty of taking care of one’s mother-in-law with dementia at home (id: Aki)

The unbalanced burden among siblings when taking care of their parents (id: Oma)

The anxiety of lacking filial piety while taking care of parents (id: Sasa)

For the next 90 minutes, the priests, experts, and participants all sat in a circle. The priests served as facilitators. First, the priests directed the conversation to those who had shared specific caregiving experiences and thoughts about caregiving in their opening self-introductions, asking for more description. Participants began talking about their experiences on the spot, gradually searching for the right words. While some participants spoke for longer, others were brief; the priests facilitated the entire process so that the participants communicated with each other on an equal footing.

Depending on the needs of the participants, we sometimes incorporated lectures by staff from government agencies or experts in community nursing and social welfare. The priests heard the needs of the participants, negotiated with the experts, and managed to incorporate their needs into the program.

3. Participants and current issues with the COVID-19 pandemic

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the KYC program was conducted face-to-face with 10 to 20 participants. The participants included family members who were currently caring for a loved one. In addition, they also comprised those who had already finished caring for a loved one and wanted to use their experience to help others, those who wanted to share their past experiences with, and those who were anxious about the possibility of caring for a family member soon. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, a similar program has been offered through an online meeting tool. Although the number of participants has dropped to 5–10, residents have expressed a need for the online meetings to continue and the face-to-face program to resume.

4. Logic model of the KYC program

A logic model of the KYC program (Figure 4) was created by the author’s team. This model was developed by referring to participants’ comments about KYC in newspapers, TV, and throughout the program observations and discussions. The model was created by the first author, who has experience in creating logic models [8]. Although it has not been examined by the strict qualitative research methods, it is comprehensively introduced here for those interested in the program.

1)Inputs/activities

The inputs/activities referred to the equipment and interventions during a KYC program. According to the logic model we developed, the program inputs/activities consisted of “Peer support” and “Expert Lectures” in the setting that Temple is “A safe place.” “A safe place” was related to the environmental aspect of the temple, where participants were safe and surrounded by people.

Notably, the place effect that temples have, as described in our logic model, may be a core element of this program. Despite providing a highly religious experience, the temple gives the impression that the participants’ behavior is observed by the higher something, as Buddha. It hears being unlike peer support programs in public places, hospitals, or nursing homes. The participants do not boast about their hardships there. They seem to surrender in a positive sense, feel that everyone is the same in the eyes of the Buddha and that they could live together, sharing both the good and the incompetence.

The location effect included the fact that the program provider or facilitator was a priest. We hypothesized that the non medical/nursing professional facilitator could provide more comfortable experience in some situations of themes. This is consistent with reports of post-disaster activities in which residents reported that having non-professional priests working side-by-side with them as fellow community members provided a sense of security and encouraged participation in the program. Although the online program has unenabled gathering at the temple, the program providers remained the same: the priests. By examining the program’s effectiveness separately from the fact that the provider is a Buddhist priest and that the program is held at a temple, a more practical and detailed evaluation of the program will be possible. Several studies have examined the effectiveness of professional education and peer support programs in Christian churches and Buddhist churches [9-11]. It may be compelling to focus on the significance of having a trusted person who originally exists in the community, such as a Buddhist priest, as the provider instead of a specialist or peer in the future.

2)Output

The outputs concerned the results of the inputs and activities. Participants could “Acknowledge each other’s current situation,” “Acquisition of self-affirmation,” and “Knowledge acquisition.” Mr. Shimomura and his colleagues observed that participants smiled more, became less tense, and were happier learning new things after the program than before.

Here is a representative comment from participants (recorded in KYC program notes).

There are places in the world where you can listen to lectures and explanations, but there are no places where you can talk about yourself, so it’s great to be able to talk here. (id: Nori, a middle-aged man)

These are limited records about participants’ changes; therefore, future research should examine them in detail. The participants’ outputs illustrated in the logic model were all described by the participants’ subjective experiences. It would be possible to capture the change. In addition, counting changes in attitudes and facial expressions by third parties may allow for a specific framing of the contributions that bring this program to life.

3)Outcome

The outcome category concerned the changes or benefits that resulted from the KYC program. It noted the immediate changes as the program outputs were expected to contribute to improvement in “Caregiver Health” and “Health of the person cared for,” as well as the <Connections between the temple and the community> in the long run. Consequently, it was thought that this experience would lead to the “Improvement of the social value of temples” and realization of “Comprehensive community care.” The long-term effect on each participant, family, or community and temple should be examined for program evaluation.

One participant reported a change in her sleep after the KYC program.

After talking here, I was able to sleep without taking medicine for the first time in a year. (id: Kuma, A bereaved older man whose spouse was his care recipient and had passed away)

Conclusions

There is limited research about the effectiveness of programs by non-professionals at temples, but community care researchers should focus on them. Temples can be expected to provide large enough land, trust from long-standing residents, high coverage to spread to rural areas, and accessibility to all religions.

In particular, accessibility, regardless of religion, will be an essential factor as the population becomes increasingly international. The aging of the foreign population in Japan is also increasing, and follow-up services for family caregivers who support them will also need to be more extensive. Future researchers may contribute to bridging the needs gap by matching the requirements of public institutions, temples, and residents.

Mr. Shimomura’s background in health sciences at university and his surrounding acquaintances have enabled him to provide peer support programs for caregivers. Many priests are not in this situation, and follow-ups with them may be necessary. First, he will need to work with the interested temple priests to implement and disseminate the program. A more detailed examination of the logic model presented here and an evaluation of immediate or long-term outcomes based on the logic model may contribute to legitimizing the program, obtaining funding and resources, and preventing the spread of poor-quality programs. Furthermore, as Woolever et al. implied, the effects of interventions may also be explained by the factors outside the temple, such as the geography of the place where it is located and relationship with other religions [12]. However, this advanced initiative challenge may be perceived as inappropriate by conservative priests. Therefore, it is advisable to focus on the relationship between temples and their position in the community to gather the pieces necessary to promote such an initiative.

Buddhism is a major religion worldwide. We believe that discussions based on international collaboration are necessary to ensure that the program is not a domestic project limited to Japan. If you are impressed by this report, we would like you to contact the first author. We will continue introducing on-time activities regularly on the first author’s web page (https://takanaruse.com/en/).

References

1.Shimomura, T. Konenji. Available online: http://konenji.tokyo/ (accessed on 15 March).

2. Summary of Report on Long-Term Care Insurance Business Status for the Fiscal Year 2019 (Annual Report), (in Japanese); 2019.

3. National Consumer Survey Overview, 2019, (in Japanese); 2019.

4. Schulz, R.; Sherwood, P.R. Physical and Mental Health Effects of Family Caregiving. The American Journal of Nursing 2008, 108 (9 Suppl), pp. 23–27. doi:10.1097/01.NAJ.0000336406.45248.4c.

5. Religious Affairs Division, Agency for Cultural Affairs. Religious Yearbook; 2020.

6. Statistics Information Department, Ministry of Health Labour. Survey of Institutions and Establishments for Long-term Care, 2017 (in Japanese); 2017.

7. Teuchi, A.; Hara, S. Contemporary Significance of Temples as Centers of Residents’ Activities: Through the Role of Temples in Community Reconstruction after the Great East Japan Earthquake. (in Japanese). Meikei Shakai Kyouiku Kenkyu 2014, pp. 2–17.

8. Naruse, T.; Kitano, A.; Matsumoto, H.; Nagata, S. A Logic Model for Evaluation and Planning in an Adult Day Care for Disabled Japanese Old People. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17 (6), 2016. doi:10.3390/ijerph17062061.

9. Johnson-Lawrence, V.; Bailey, S.; Sanders, P.E.; Sneed, R.; Angel-Vincent, A.; Brewer, A.; Key, K.; Lewis, E.Y.; Johnson, J.E. The Church Challenge: A Community-Based Multilevel Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial to Improve Blood Pressure and Wellness in African American Churches in Flint, Michigan. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2019, 14, pp. 100329–100329, doi:10.1016/j.conctc.2019.100329.

10. Krause, N. Receiving Social Support at Church When Stressful Life Events Arise: Do Catholics and Protestants Differ? Psycholog Relig. Spiritual. 2010, 2 (4), pp. 234–246. Doi:10.1037/a0020036.

11. Pengpid, S.; Peltzer, K.; Jayasvasti, I.; Aekplakorn, W.; Puckpinyo, A.; Nanthananate, P.; Mansin, A. Two-Year Results of a Community-Based Randomized Controlled Lifestyle Intervention Trial to Control Prehypertension and/or Prediabetes in Thailand: A Brief Report. Int J Gen Med. 2019, 12, pp. 131–135. doi:10.2147/ijgm.S200086.

12. Woolever, C.; Bruce, D. Places of Promise: Finding Strength in Your Congregation’s Location; Westminster John Knox Press: Louisville, Ky, 2008.